How Gandhi & Nehru Created Ashoka the Great

A deep dive into emperor Ashoka's story and what really happened after the Kalinga war.

We’ve all heard the story of Ashoka the Great.

It’s one of those stories that gets taught early and is repeated often - in history books, in schools and in popular culture. Shah Rukh Khan played him in a Bollywood film. His Lion Capital is our national emblem and appears on our currency and every government document.

If you grew up in India, you know the story by heart. A ruthless emperor conquers Kalinga in a brutal war. The bloodshed horrifies him. He converts to Buddhism, gives up violence and spends the rest of his life ruling peacefully, building hospitals, planting trees and protecting animals.

The warrior who became a saint. Simple and inspiring. It’s a perfect story.

Except… there’s a problem. We don’t actually know if that’s how it happened.

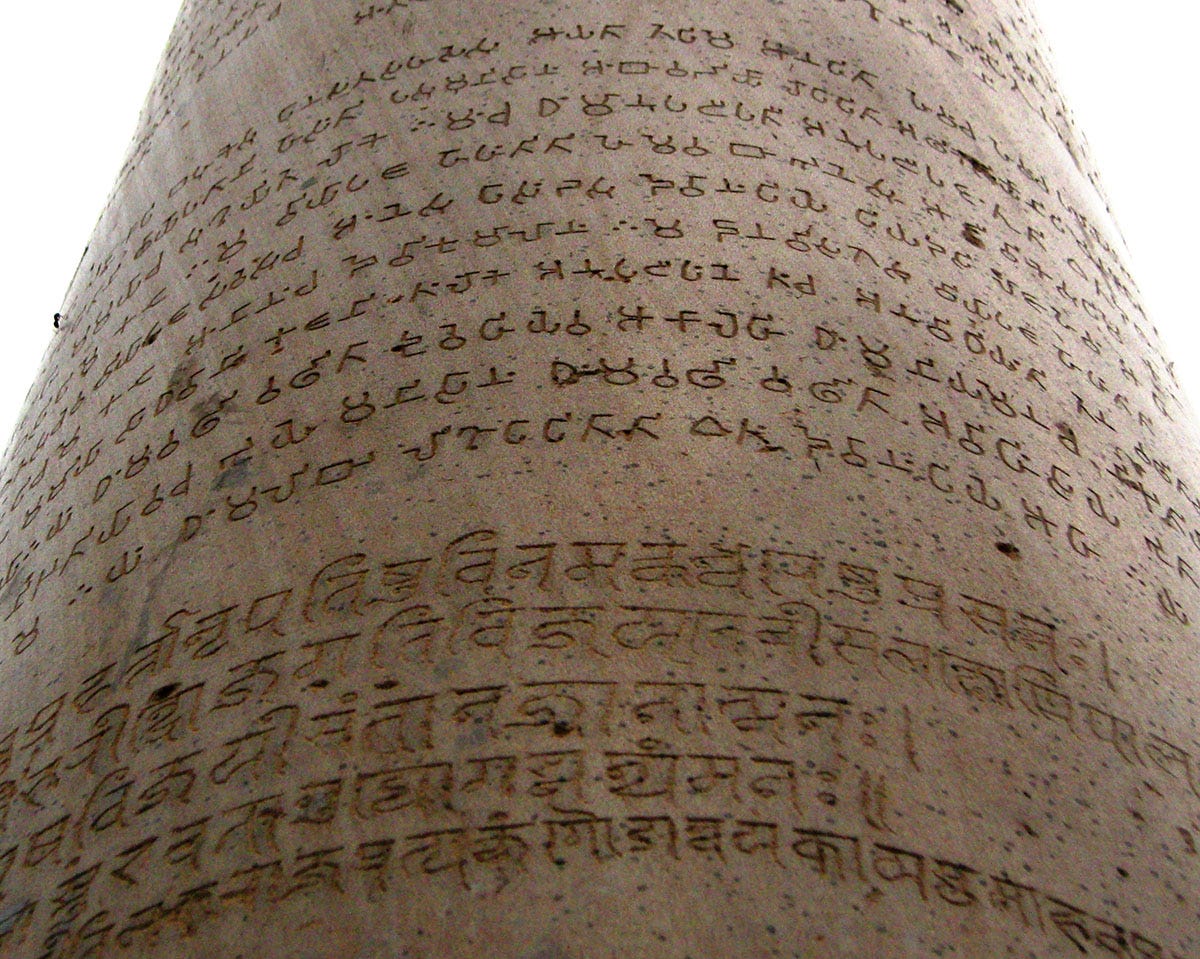

You see, Ashoka lived over 2,300 years ago. The sources that talk about him are limited and contradictory. There are his inscriptions (carved on rocks and pillars across his empire). But these are essentially ancient press releases - public messages carefully crafted to shape his image.

Then there are Buddhist texts written centuries after his death. These glorify both Ashoka and Buddhism, so they paint him as a monster before his conversion, to make his transformation seem miraculous. And then there’s some scattered archaeological evidence and mentions in other religious texts.

Each source tells a slightly different story. Each has its own agenda. And the ‘truth’ is somewhere in the messy middle.

So what I’m going to do is tell you what we actually know about Ashoka - the parts that are history, the parts that are probably legend, and the parts where we’ll never know for sure.

And in the process, we’ll discover how Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru played a huge role in making Ashoka a symbol of Indian pride.

A quick note before we begin:

I’m not a historian, so take everything I write with that in mind. But this post comes from genuine research - I spent several days going through books, summaries of Buddhist texts, and reading the English translations of Ashoka’s actual edicts (you can find the link at the end).

My goal was to find out how much of Ashoka’s story (the one we’ve all been told) is actually true.

This is also the first post in my Kings of India series. Over the next few weeks, I’ll be writing about some of the most fascinating rulers from Indian history - the ones whose stories are too good not to share.

Now, onto Ashoka the Great…

Ashoka was born around 304 BCE into one of the most powerful families in India.

His grandfather, Chandragupta Maurya, had built the Mauryan Empire from scratch - a massive centralized empire stretching from Afghanistan to Bengal. His father, Bindusara, expanded it even further south. By the time Ashoka came along, the Mauryan Empire controlled nearly the entire subcontinent.

But being born into royalty didn’t automatically make Ashoka special. His father had multiple wives and dozens of children. Technically, they were all special and in line for the throne. But realistically, only one of them mattered - Susima, the eldest son and the crown prince.

Ashoka was just another prince among many. And if Buddhist texts are to be believed, he wasn’t even an impressive one. At least, not to look at.

The Ashokavandana, a Buddhist text written centuries after Ashoka’s death, describes him as having ‘coarse looks and a harsh demeanour.’ Not handsome. Not charming. Just… rough.

The same text claims Bindusara disliked him because of his appearance and always favoured the polished, princely Susima instead.

Take this with a grain of salt. These Buddhist texts were written hundreds of years after Ashoka died, and they had an agenda. They painted young Ashoka as flawed, ugly, unlikable and cruel to make his transformation more dramatic.

But there’s probably some truth buried in there. Royal courts were obsessed with appearances, and Ashoka likely wasn’t the most handsome prince.

What Ashoka did have, though, was skill.

Most sources agree on this. Ashoka was exceptionally capable. Good at administration, good at military strategy and good at getting things done. And Bindusara, despite whatever personal feelings he had, recognised this.

When a revolt broke out in Taxila (now in Pakistan), an important city for the empire, the local governors couldn’t suppress it. So, Bindusara sent his capable but unloved son to do the job.

Ashoka succeeded.

After that, he was made governor of Ujjain, an important trading center in central India. Again, this wasn’t a ceremonial position to keep him busy. Ujjain mattered, and Binusara clearly trusted Ashoka to run it.

Which raises an interesting question. If Bindusara really disliked Ashoka as much as legends claim - why did he keep giving him important jobs?

Maybe the legends exaggerated the tension between them. Or maybe Bindusara was just realistic - he didn’t like Ashoka, but he needed his skills. Or maybe keeping Ashoka far away from the capital city was strategic - a way to keep him away from politics and succession. We’ll never really know.

What we do know is that for years, Ashoka governed distant provinces while his brother, Susima, stayed at the capital city, being groomed to rule the empire.

Then, in 273 BCE, Bindusara died.

When Bindusara died, the question was - who would succeed him?

The obvious answer was Susima. He was the crown prince, groomed for this his entire life. But obvious doesn’t always mean guaranteed, especially when you have dozens of ambitious princes who’ve spent years governing smaller provinces and commanding armies.

Ashoka was one of them.

What exactly happened over the next few years is unclear. We don’t have a detailed account of the succession struggle, just fragments from various sources.

The Buddhist texts tell a dramatic story. They claim Ashoka killed Susima and then went on a killing spree, massacring 99 of his brothers to eliminate any rivals. Another text says he killed all his brothers (more than 100) and only spared his youngest full brother. Some texts paint an even bloodier picture of the succession as well.

It makes for a compelling story. The ugly, unloved prince butchering his way to the throne. But there’s a problem with these stories. Ashoka’s own edicts (inscriptions he’d later carve across his empire) mention something different.

(We’ll get to what these edicts are later - keep reading and you’ll find out.)

In Rock Edict V, he talks about appointing officials to look after “the welfare of the families of his brothers and sisters.” If he had killed all of his brothers, whose families would be caring for?

The math doesn’t add up. Some of his siblings clearly survived. Maybe several of them did.

So what probably happened? Ashoka killed Susima - that much seems certain. Susima was the crown prince, the legitimate heir, and he stood in Ashoka’s way. Ashoka likely killed a few other rivals too, brothers who had their own ambitions or who backed Susima.

But 99 brothers? That’s just the Buddhist texts exaggerating Ashoka’s pre-conversion cruelty.

The succession fight was probably brutal and took years. Some texts mention a gap of four years between Bindusara’s death and Ashoka’s formal coronation, suggesting a long conflict.

By 268 BCE, Ashoka had won. He was now the third emperor of the Mauryan dynasty, ruling over an empire that stretched from Afghanistan to Bengal. Nearly the entire subcontinent answered to him. Nearly.

There was one significant gap, though - Kalinga, a prosperous kingdom on the eastern coast, roughly where the modern state of Odisha sits today.

Kalinga was a wealthy, well-organised kingdom that controlled important trade routes connecting India to Southeast Asia. Its fertile lands produced rice and other valuable goods. And perhaps most importantly, it sat right in the middle of the empire’s eastern territory, an independent kingdom surrounded by Mauryan provinces.

Both Ashoka’s grandfather and father had tried to conquer it. Both had failed. And for eight years, even Ashoka left it alone. He managed his own empire and ruled the way Mauryan emperors always had.

But by 260 BCE, in the eighth year of his reign, he decided that Kalinga needed to be brought under Mauryan control. Maybe it was strategic. Maybe it was pride. Or maybe it was just what emperors did.

Whatever his reasoning, Ashoka marched his armies toward Kalinga.

It would be the last war he ever fought.

The war with Kalinga was brutal.

We don’t have detailed accounts of the fighting itself but we know it was devastating. Archeological excavations in Kalinga have found burnt fortifications, layers of ash and mass graves.

Ashoka’s armies clearly overwhelmed Kalinga’s defence. Cities fell, forts were destroyed and its army was crushed. When it ended, Kalinga was no longer independent. It belonged to the Mauryan empire.

Years later, Ashoka would write about this war. Not in private letters or official records, but in public inscriptions carved on rocks and pillars across his empire. These inscriptions are known as Ashoka’s edicts.

These edicts were scattered across his kingdom. From Afghanistan to Karnataka to Bengal, they had Ashoka’s messages carved and placed along major roads and near important cities where people would see them.

What’s more interesting is that they were written in a local language that ordinary people could actually read. Not in Sanskrit, the language of priests and scholars. His goal was obviously to reach as many people as possible.

And more importantly, they were written in Ashoka’s own voice, like he’s having a conversation with the people. He addresses his subjects directly. He explains his thinking. And he admits his mistakes.

No other ancient ruler left behind anything like this.

You can read the English transcription of his edicts in the link attached at the end of this post.

In one of the edicts - Rock Edict XIII - Ashoka described what happened in Kalinga.

“One hundred thousand were killed, one hundred and fifty thousand were deported, and many more died from other causes.”

That’s not a historic estimate. That’s the emperor himself, publicly admitting to the scale of death and suffering he had caused.

He continues:

“After the Kalingas had been conquered, Beloved-of-the-Gods (Ashoka) came to feel a strong inclination towards Dhamma (teachings of Buddha), a love for Dhamma and for instruction in Dhamma. Now Beloved-of-the-Gods feels deep remorse for having conquered the Kalingas.”

This was extraordinary. Conquerors from history didn’t publicly confess regret for their victories. But Ashoka carved these words on rocks across his empire for everyone to read.

Except in Kalinga.

Rock Edict XIII, with its detailed confession of remorse, appears all over Ashoka’s empire. You can find it in the north, in central India and in the south.

But in Kalinga? Nothing, No Rock Edict XIII. No public apology.

Instead, in Kalinga, Ashoka placed different edicts. Instructions to his officials on how to govern, how to treat people with compassion, how to win them over through Dhamma. Practical guidance, but no confession of remorse.

Why tell everyone else about your guilt except the people who actually suffered through the war?

Maybe he thought it would undermine his authority. Maybe telling Kalingans, “I feel terrible about this, but I’m still your emperor” seemed politically wrong. Or maybe the remorse, while genuine, was also strategic, a message crafted for distant subjects who could’t verify what actually happened.

We’ll never know for sure.

What we do know is that something changed in Ashoka after the Kalinga war. This was the last war he ever fought.

So, what happened after the war?

The popular story is simple and dramatic. Ashoka walks through the aftermath of the Kalinga war, sees the devastation he’s caused and has an immediate spiritual awakening. Horrified by the bloodshed, he gives up violence on the spot and converts to Buddhism.

It’s a great narrative. But Ashoka’s own edicts tell a different story.

In a Minor Rock Edict issued in his 13th year as emperor, Ashoka writes that he had been a Buddhist follower for “more than two and a half years” but admits he “did not make much progress” initially. Only in the past year, he says, had he drawn closer to the Buddhist monks and become more devoted.

Do the math. Year 13 minus 2.5 years means Ashoka became Buddhist around year 10 or 11 of his reign. The Kalinga war happened in year 8.

So according to his own words, Ashoka converted roughly two to three years after the war, not immediately. And even then, his transformation was gradual. He didn’t wake up the day after Kalinga as a devoted Buddhist. It took time.

This story gets even more complicated as you read the Buddhist texts from Sri Lanka. They tell a completely different story.

They claim Ashoka converted to Buddhism in his fourth year as emperor, well before Kalinga. By his seventh year, they say, he’d already built 84,000 monasteries across his empire. According to these texts, Ashoka was already a devoted Buddhist when the Kalinga war happened.

Which raises a question: if Ashoka was already Buddhist, already committed to non-violence, how do you explain him slaughtering 100,000 people in year 8?

The Buddhist texts have an interesting way to get rid of these doubts. They barely mention the Kalinga war. It’s skimmed through or ignored completely.

So which version is true?

Well, most historians trust Ashoka’s own account. The edicts were written during his lifetime, they are concrete evidence, not stories written centuries later. And they clearly state that his conversion came after the Kalinga war and developed gradually.

The Buddhist texts, written hundreds of years after Ashoka died, had their own agenda. They wanted to portray Ashoka as the ideal Buddhist king, and a Buddhist king who massacres 100,000 people is hard to explain. So they simply didn’t talk about the violence at all.

I personally would go with this version: Ashoka didn’t become a saint overnight. He became one slowly, deliberately, over years of reflection and practice. And once he did, he was completely committed to Buddhism. Well, kind of.

Once Ashoka committed to Buddhism, he made it central to how he governed.

His edicts describe important changes in his policies. He ordered the planting of trees along roads to provide shade for travellers. He had wells dug at regular intervals. He built rest houses for people on long journeys. He built hospitals, for both humans and animals. He even imported medicinal herbs that weren’t locally available.

In Pillar Edict II, he writes:

“Everywhere I have made provision for two types of medical treatment: medical treatment for humans and medical treatment for animals.”

He restricted animal slaughter. Certain animals were declared protected. The royal kitchens were ordered to drastically reduce animal killing. Hunting for sport was also banned.

He promoted religious tolerance. In Rock Edict XII, he says: “All religions should reside everywhere, for all of them desire self-control and purity of heart.” He gave gifts to Buddhist monks, and also to Brahmins, Jains and Ajivikas. He appointed officers specifically to ensure different religious communities were treated fairly.

This was genuinely progressive for the time. Most ancient rulers either ignored religion or favoured their own. Ashoka actively promoted respect for all faiths.

He even sent missionaries to spread Buddhism beyond India’s borders. The Buddhist texts claim he sent his own son, Mahendra, to Sri Lanka, though this detail doesn’t appear in Ashoka’s own edicts. What we do know is that Buddhism did spread to Sri Lanka around this time, and Ashoka likely played a role in that.

By all accounts, Ashoka became a devoted Buddhist who genuinely tried to align his governance with Buddhist principles. But like everything else in his story, this also gets a little complicated.

In the same Rock Edict XIII where Ashoka expresses remorse for Kalinga, he also includes a warning to the “forest tribes” on his borders. Despite his regret, he writes, he still possesses “power to punish them” if they misbehave.

He kept his army. He changed the death penalty - giving prisoners a three-day period to settle their affairs - but he didn’t abolish executions entirely.

And then, there are stories claiming Ashoka turned violent against other religions. Some Buddhist texts (particularly the Ashokavadana) claim that after converting to Buddhism, Ashoka became intolerant of other religions. One story says he ordered the execution of 18,000 Ajivikas after one of them drew an offensive image of Buddha. Another claims he put a bounty on Jain heads, which accidentally led to his own brother (who had become a monk and was mistaken for a Jain) being killed.

If true, these stories contradict everything Ashoka said about religious tolerance. But these stories appear only in Buddhist texts written centuries after Ashoka died. They don’t appear in Jain writings from that period, which actually mentions Ashoka favourably. They don’t even appear in his own edicts, which promote respect for all religions.

Most historians think these stories are either propaganda from later Buddhist-Jain conflicts or dramatic inventions meant to add complexity to Ashoka’s character.

So what can we make of all this?

Well, for me at least, Ashoka wasn’t a hypocrite and his Buddhist conversion was not fake. His policies were real. His religious tolerance was real. And his remorse was real.

But he also understood that running a vast empire sometimes required force. He promoted non-violence as an ideal while keeping his army ready. He preached compassion while maintaining the power to punish. He advocated for religious tolerance while being deeply committed to Buddhism.

He was not trying to be a saint. He was just trying to rule a massive, diverse empire through moral authority while still keeping the traditional tools (like his army) in reserve. It was a delicate balance. And as it turned out, it wouldn’t survive him.

Ashoka died around 232 BCE after ruling for roughly 37 years.

Buddhist legends say that in his last days (when he was sick), Ashoka kept giving away his wealth to Buddhist monks and monasteries. His ministers, alarmed at the emptying treasury, eventually stopped him from accessing state funds. So, Ashoka started giving away his personal possessions - jewellery, clothes or anything else of value. When those ran out, the story goes, all he had left was half a fruit. He gave that away too, his final offering to the Buddhist monks.

It’s a beautiful story. Whether it’s true or not, we’ll never know.

What we do know is that the empire Ashoka built didn’t survive after him. He was succeeded by one of his sons or a grandson; the sources are unclear. And within fifty years of Ashoka’s death, the empire had collapsed completely. Even Kalinga regained its independence.

The Dhamma-based governance Ashoka had spent decades building also fell apart. And then, gradually, Ashoka himself was forgotten.

Over the centuries, the Brahmi script used in his edicts became unreadable. New scripts replaced it. The language changed. The pillars and rocks remained, but nobody could understand what they said anymore. Ashoka’s name survived in Buddhist texts preserved in Sri Lanka and Tibet, but in India, he faded from memory.

For over 1,500 years, one of India’s greatest emperors was completely forgotten. Until 1837, when a British scholar named James Prinsep decoded the inscriptions.

I’ve written about James Prinsep and how he cracked the Brahmi script before - you can read that full story here.

But what matters for Ashoka’s story is that his rediscovery in the 19th century set the stage for him to become something he’d never been during his lifetime. A symbol of Indian identity itself.

In the early 1900s, as India’s independence movement gained momentum, Indian nationalists were searching for historical figures who showed India’s strength. The British portrayed India as chaotic and incapable of self-rule. Ashoka became the perfect answer to this.

For Mahatma Gandhi, Ashoka was proof that non-violence wasn’t a foreign concept. It was authentically Indian, rooted in India’s own history. Here was an Indian emperor who had given up violence 2,300 years ago, who had promoted compassion and tolerance, who had built a vast empire and then chosen peace over conquest. Gandhi spoke of Ashoka often, holding him up as an example of ahimsa in practice.

For Jawaharlal Nehru, Ashoka represented a blueprint for what independent India could become. He saw in him a model of secular governance, where the state respected all religions without favouring any. He saw a ruler who cared about public welfare, building hospitals, planting trees and digging wells. In his book “The Discovery of India,” Nehru wrote that Ashoka “represents a radiant chapter in Indian history.”

On 26 January 1950, after independence, a representation of the Lion Capital of Ashoka placed above the motto, Satyameva Jayate, was adopted as the State Emblem of India.

The choice of using Ashoka’s symbols sent the message that India would be secular, committed to non-violence and ethical governance. Everything Ashoka represented in the nationalist imagination became what India aspired to be.

But in the process, the complex and contradictory Ashoka we’ve been discussing got simplified. The story became streamlined. Ruthless emperor sees horrors of war, converts to Buddhism instantly, becomes compassionate and rules through pure non-violence. Clean. Simple. Inspiring.

The messy timeline of his conversion? Simplified. The contradiction about his remorse and the edicts missing from Kalinga? Not mentioned. The warnings about still having “power to punish”? Left out. The fact that his system collapsed almost immediately after his death? Ignored.

Not because anyone was deliberately lying. But because the story served a purpose. A newly independent nation needed heroes. It needed symbols. It needed proof that Indian civilization had produced great, ethical rulers who could stand alongside anyone in world history.

And Ashoka - simplified, idealized, perfected - became that symbol.

That’s how Ashoka became - Ashoka the Great.

Note: You can read the english translation of all of Ashoka’s edicts here.

It was a powerful symbol, and a successful identity was created with the Ashokan story. Since the 1950s, historians have uncovered a more layered and nuanced picture of Ashoka’s life, yet our textbooks have scarcely been updated to reflect that knowledge.

Today, with Modi, whose legacy is inseparably tied to the Gujarat riots, his hostility to Nehru, and the RSS ideology that schooled him, the old symbols of non-violence and secularism are being deliberately erased. The lathis, the “bunch of thoughts,” the blunt tongues: these are the new instruments of nation-making. If Ashoka, Gandhi, and Nehru are declared irrelevant, the question is not just what replaces the pillar, but what kind of India emerges when violence and exclusion, rather than restraint and pluralism, become the pillars of the nation.

Thank you so much! I loved reading this. Will read it again at night. I look forward to your series on Indian kings. I wonder if you’re including hindu kings only or both Hindu and muslim?

This is such important work, btw, writing about history without agenda, without picking a side.

Please read my ten letter series to India, the first one has a bit about Asoka. Would really like to hear your thoughts on it.