How Monopoly Became a Monopoly

The story of how a board game designed to fight monopolies became one of the most successful monopolies ever.

There’s nothing quite like the feeling of owning Boardwalk and Park Place in Monopoly.

You know exactly what I’m talking about.

Your friend lands on your property, and you get to watch their face as you announce the rent: “That’ll be 200, please. Oh wait! Actually, I have a hotel built on it, so that’ll be 2000.”

The look on their face as they count those colourful notes and hand them over is priceless.

I love everything about Monopoly. The negotiations, the thrill of completing a colour group and the satisfaction of collecting rent from properties you’ve been building for hours. There's something satisfying about creating your little real estate empire and watching your bank account grow while your friends slowly go broke.

It's capitalism in its purest, most entertaining form - and I absolutely love it. But recently, I discovered something about the origins of Monopoly that left me baffled!

What if I told you that Monopoly was originally created to show why everything I just described is exactly what's wrong with capitalism?

You guessed it - today we’re diving into the fascinating history of Monopoly, the board game that’s probably caused more arguments than any other piece of cardboard in existence.

This is the story of how one woman’s attempt to teach people about the dangers of capitalism ended up creating the ultimate celebration of… capitalism.

So, how did a game designed to critique monopolies become... well, a monopoly itself?

The story begins in 1903, with a woman named Elizabeth Magie sitting in her apartment, sketching out the design for what would eventually become one of the world's most famous board game.

You see, Elizabeth was obsessed with a book called “Progress and Poverty” by economist Henry George. His central argument in the book was that, despite the progress and economic growth of the late 1800s in America, poverty was actually getting worse. Why? Because wealthy landowners were monopolising property, charging high rents and getting richer. While everyone else got poorer.

This idea consumed Elizabeth. She was a brilliant woman who believed that if people could just see how landlord monopolies worked, they'd demand change. But how do you make an abstract economic theory feel real?

By making a board game, duh!

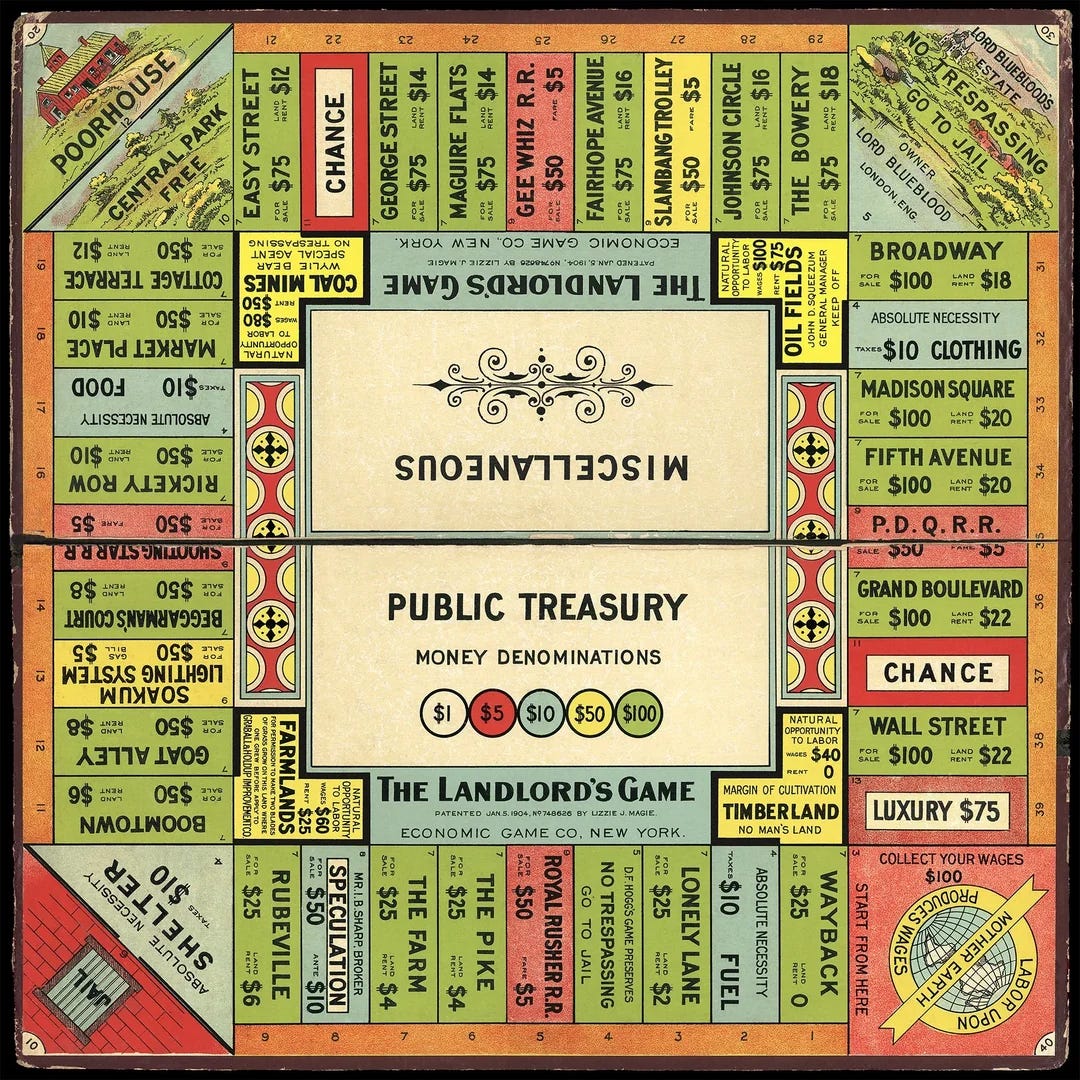

So, she created a board game that would let people experience both sides of this economic theory. And in 1904, she patented “The Landlord’s Game.”

In the game, players would roll the dice, move their pieces and land on different spaces. Some spaces were properties they could buy, like vacant land, houses, even railroads and utilities. And once they owned a property, anyone else who landed on it had to pay them rent. The goal was to accumulate as much wealth as possible while avoiding bankruptcy.

If this sounds exactly like Monopoly, that's because it basically was Monopoly. The Landlord's Game had everything the modern-day Monopoly has - the square board, the property-buying, the rent payments, chance cards, even a "Go to Jail" space and money for passing the starting corner.

But Elizabeth had designed two completely different sets of rules to play the game.

The first set of rules worked exactly like the Monopoly we know today - players competed ruthlessly to bankrupt each other. Winner takes all. She called these the “Monopolist” rules.

The second set of rules were completely different. Let’s call them the “Anti-Monopolist” rules - players shared wealth, everyone benefited when someone made money and the goal was collective prosperity rather than individual domination.

She assumed that people would try both versions and immediately realise that the ‘Anti-Monopolist’ version of the game was more fun, more fair and more satisfying.

But there was just one small problem… nobody wanted to play the Anti-Monopolist version.

When Elizabeth introduced The Landlord’s Game to friends, activists and economic students, they would politely listen to her explanation of both sets of rules. They would nod along as she described the benefits of the Anti-Monopolist version. But then they would immediately ask to play with the Monopolist rules instead.

Turns out, people didn't want to experience shared prosperity and economic fairness. They wanted to crush their opponents, charge outrageous rents and watch their friends go bankrupt.

Her educational tool had backfired. Instead of teaching people that monopolies were evil, she had accidentally created the most entertaining monopoly simulator ever invented. The “Anti-Monopolist” rules were forgotten almost immediately, while the “Monopolist” version spread like wildfire through colleges, social clubs and other communities across America.

By the 1920s, people were making their own homemade versions of the game, often not even knowing it was called “The Landlord's Game” or that someone named Elizabeth had created it. They called it "Monopoly" and passed it along to friends, with each group adding their own local touches and variations.

One community in Atlantic City decided to make the game more personal by swapping out Elizabeth’s generic property names for streets they actually knew.

Mediterranean Avenue and Baltic Avenue became the cheap properties because they were in the poorer part of the town. Boardwalk, a famous street where wealthy tourists strolled, became the most expensive property on the board.

They added more ‘chance cards’ and ‘community chests’ that could either help or hurt players during the game. They even organised the properties into colour groups, so the players could charge higher rent on collecting the properties of the same colour.

One of the most dedicated players in Atlantic City was a man named Charles Todd. He was so enthusiastic about the game that he spent hours creating his own handmade version. He drew the board by hand, wrote out all the property names and even created his own money, cards and playing pieces.

While writing the property names on his board, Todd made one tiny mistake. He accidentally spelled “Marven Gardens” as “Marvin Gardens” - an error that can still seen on the modern versions of the game.

Anyway, Todd's homemade board, complete with the typo, became the version that his friends and family played with for years. And in 1933, when Todd had some friends over for dinner, he taught the game to a new guest.

That guest was Charles Darrow, an unemployed engineer who was struggling to make ends meet during the Great Depression.

Darrow had never seen anything like Todd's game before. As the evening went on, he watched everyone buy properties, collect rent and try to bankrupt each other. He was fascinated. The game was entertaining, sure, but Darrow saw an opportunity.

When the night ended, Darrow asked Todd if he could get a written copy of the rules. Todd was happy to oblige. After all, the game was more fun when more people knew how to play it. He wrote down all the rules, drew a rough sketch of the board layout and handed it over to Darrow.

Darrow took those handwritten rules home, copied Todd's board exactly (including the “Marvin Gardens” typo), and began making his own sets. But unlike Todd, who had shared the game freely with friends, Darrow was going to sell it.

By 1934, Darrow had created several sets of his “Monopoly” game and had decided to approach Parker Brothers, a well-known toy company of the time. He walked into their office with his handmade set and pitched “Monopoly” as his original creation.

Unfortunately for him, Parker Brothers rejected the game immediately. They thought that the game was too complicated, took too long to play and had some fundamental design flaws.

But Darrow was not discouraged. He went back home, continued making sets on his own, and started selling the game through local departmental stores and by word of mouth. The game caught on. By Christmas 1934, he had sold around 5,000 copies.

This success caught Parker Brothers’ attention. When they saw how well Darrow's game was selling, they struck a deal with Darrow to buy the rights to “Monopoly.”

The timing couldn't have been better. Families struggling through the Great Depression found a game that let them fantasize about owning property and getting rich. By the end of 1935, Monopoly had become a sensation in America.

But as sales soared, Parker Brothers started receiving letters from people across America claiming they had played similar games years before Darrow's “invention.” Some wrote in saying they remembered playing Monopoly" in college back in the 1920s. Others mentioned homemade versions they'd seen at friends' houses.

This was a problem. Parker Brothers had just paid Darrow for the rights to what they believed was his original creation, but something seemed fishy. When they confronted Darrow, they received vague, contradictory answers that didn't add up.

They were already making good money from Darrow’s game and didn’t want to risk losing it. So, they launched a quiet investigation to track down anyone who might have a legitimate claim to Monopoly.

As they traced the game's path backwards, from Charles Darrow to Charles Todd in Atlantic City, to college campuses, they found the original inventor. A 70-year-old woman named Elizabeth Magie, who seemed to have a patent for a very similar game.

George Parker, one of the Parker Brothers, personally visited Elizabeth at her home to offer her $500 for her patent to The Landlord's Game. More importantly, he made her a promise: Parker Brothers would publish a new edition of The Landlord's Game and give her proper credit as an inventor of the game.

For Elizabeth, this seemed like her moment had finally arrived. After more than 30 years of watching her creation spread anonymously across the country, she would finally get the recognition she deserved for her brainchild. She signed the deal.

But Parker Brothers didn't stop there. They went on to buy the rights to every other Monopoly-like game they could find. And within months, Parker Brothers had achieved a complete monopoly on Monopoly itself.

Now that they had the rights to all Monopoly-like games and patents, they marketed their game aggressively. Every Monopoly box now told the heartwarming story of Charles Darrow, an unemployed man who invented the game in his basement during the Great Depression.

It was the perfect ‘American Dream’ narrative, and it worked. Monopoly was a success.

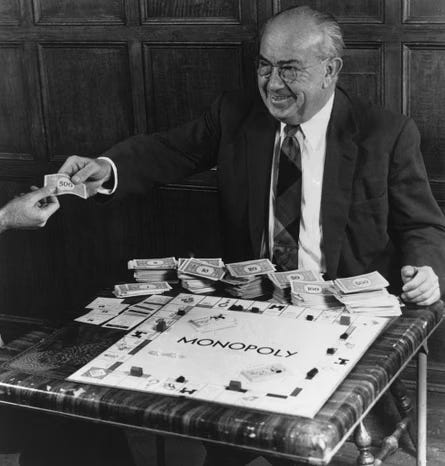

Parker Brothers were definitely getting rich, but so was Charles Darrow. Like really rich. The man who had learned the game at a dinner party was now earning royalties on every Monopoly set sold. By the late 1930s, he had become one of the first millionaires in the board game industry.

And Elizabeth Magie? Well, she lived quietly with her $500. Parker Brothers did technically fulfill their promise to her. They published a new edition of ‘The Landlord's Game.’ But they gave it zero marketing, minimal distribution and let it die quietly. Elizabeth died at the age of 81, never knowing that millions of people around the world played her game every night.

For the next 25 years, nobody questioned the Charles Darrow story. The myth was complete, and Parker Brothers' secret was safe.

Until someone created Anti-Monopoly.

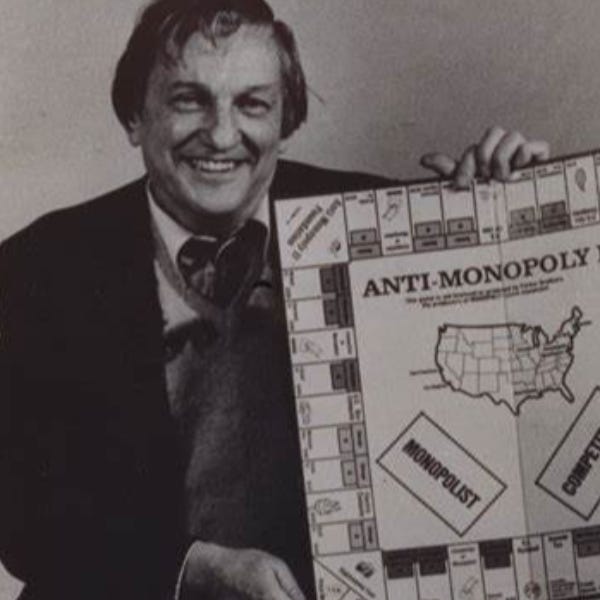

In 1973, economics professor Ralph Anspach was teaching his students about antitrust laws - the rules that are supposed to prevent big companies from becoming too powerful and crushing all their competition.

He wanted to teach them the difference between healthy competition (where multiple companies compete and consumers benefit) and harmful monopolies (where one company dominates everything and can charge whatever they want).

So, how do you teach something so abstract and boring? You know the answer by now…

A board game, duh!

He created “Anti-Monopoly” - a game where players were divided into two teams. Half played as monopolists trying to dominate markets and crush competitors. The other half played as competitors, trying to break up those monopolies and restore fair competition. The goal was to show students that competition benefits everyone, while monopolies only benefit the company that controls them.

Sounds familiar? That’s because it was essentially the same lesson Elizabeth Magie had tried to teach 70 years earlier, just with a modern twist.

Ralph’s game was a hit with his students, so he decided to sell it commercially. But there was a small problem. Turns out, you couldn’t simply use the word “Monopoly” in a game’s name.

Parker Brothers had spent decades ensuring they owned the rights to anything Monopoly-related. They weren't about to let some economics professor profit off their efforts. So, they sued Ralph for trademark infringement.

And what followed was a legal war that lasted nearly a decade.

Ralph’s legal team realised that the only way to win the case was by proving that Parker Brothers or Charles Darrow didn’t actually invent monopoly-type games. That meant digging into the real history of Monopoly.

They dug through old records, patents, newspaper archives, and followed the trail from Charles Darrow back to Charles Todd, to college campuses across America.

Eventually, they discovered the truth: Elizabeth Magie had invented the game in 1903, thirty years before Charles Darrow. The heartwarming story of the unemployed man inventing Monopoly during the Great Depression was completely false. Darrow had simply copied an existing game and claimed it as his own creation.

In 1975, the real story finally broke. A news channel aired a segment exposing Parker Brothers' decades-long cover-up. Newspapers across America ran headlines about the forgotten woman inventor whose creation had been stolen and whose name had been erased from history.

After 40 years of being forgotten, Elizabeth Magie finally got the recognition she deserved. Though she had been dead for nearly 30 years.

In 1979, Ralph won the case. The court ruled that ‘Monopoly’ had become a generic term for a type of board game, just like ‘chess.’ Parker Brothers' trademark was invalid. After decades of legal protection, they had lost the exclusive right to the name “Monopoly.”

It was a stunning victory. Ralph Anspach, the economics professor who just wanted to teach his students about competition, had taken on one of America's biggest toy companies and won.

But Parker Brothers were not done fighting. They used their political connections, and in 1984, the American government passed a special law that restored Parker Brothers’ trademark rights.

Ralph was allowed to continue selling Anti-Monopoly as an exception, but “Monopoly” remained the exclusive property of Parker Brothers.

And so, more than 80 years after Elizabeth Magie first sketched out her educational board game, the ultimate irony was complete. Her anti-monopoly game had become the one of the most successful monopoly in entertainment history. A global empire worth millions (or perhaps billions) of dollars.

The woman who wanted to teach people that monopolies were evil had accidentally created the perfect monopoly.

Her educational tool worked, though. Just not the way she intended. Instead of teaching us to hate monopolies, she showed us how much fun bankrupting your friends really is.

What an unbelievable story! The irony is just too good. The story also goes to show how the best ideas comes from books.

I was hooked from the start. Thanks for writing!

It was wonderfully written. Basic philosophy of the game along with the chronological history was amazingly depicted. I knew a little bit of it. Now I get the entire thing at one place. Thanks for the writing.